Michelangelo’s Prisoners or Slaves

The “Awakening Slave” and “Young Slave” by Michelangelo

The fame of these four powerful statues – named by scholars as “The Awakening Slave”,“The Young Slave”,“The Bearded Slave” and “The Atlas (or Bound)” – is due above all to their unfinished state. They are some of the finest examples of Michelangelo’s habitual working practice, referred to as “non-finito” (or incomplete), magnificent illustrations of the difficulty of the artist in carving out the figure from the block of marble and emblematic of the struggle of man to free the spirit from matter. These sculptures have been interpreted in many ways. As we see them, in various stages of completion, they evoke the enormous strength of the creative concept as they try to free themselves from the bonds and physical weight of the marble. It is now claimed that the artist deliberately left them incomplete to represent this eternal struggle of human beings to free themselves from their material trappings.

The “Bearded Slave” and “The Atlas” by Michelangelo

As you admire the Prisoners from different angles, one can notice Michelangelo’s love and understanding of the human anatomy. The Prisoners’ heads and faces are the least-developed parts, but they are to communicate with their poses, known as the classic “contrapposto” (counter pose). The Slaves are standing with most of their weight on one foot so that their shoulders and arms twist off-axis from the hips and legs. This precise pose gives the Prisoners a more dynamic and powerful appearance, transmitting motion and emotion.

Michelangelo’s non-finito

All the unfinished statues at the Accademia reveal Michelangelo’s approach and concept of carving. Michelangelo believed the sculptor was a tool of God, not creating but simply revealing the powerful figures already contained in the marble. Michelangelo’s task was only to chip away the excess, to reveal. He worked often for days on end without sleep, keeping for days his boots and clothes, as reported in Vasari’s chronicles about Michelangelo’s passion and talent. One can clearly recognize the grooves from mallet and pointed chisel on the marble surface used in this initial stage. Unlike most sculptors, who prepared a plaster cast model and then marked up their block of marble to know where to chip, Michelangelo mostly worked free hand, starting from the front and working back. These figures emerged from the marble “as though surfacing from a pool of water”, as described in Vasari’s “Lives of the Artists”. The method was to take a figure of wax, lay it in a vessel of water and gradually emerge it, noticing the most prominent parts. Just so, the highest parts were extracted first from the marble.

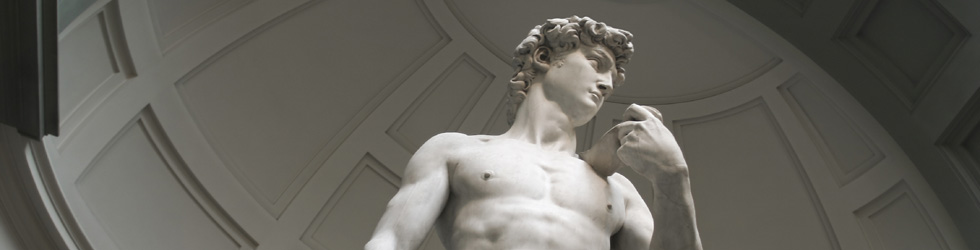

The Awakening Slave

The Awakening Slave (marble, height 267 cm, circa 1520-23)

This piece is one of the most powerful and expressive works among the Slaves. It is the first statue one finds on the left along the corridor, the least outlined of the four Prisoners. The figure feels like it is writhing and straining, trying to imminently explode out of the marble block that holds it. The latent power one feels is extraordinary. Michelangelo is famous for saying that he worked to liberate the forms imprisoned in the marble. He saw his job as simply removing what was extraneous. This endless struggle of man to free himself from his physical constraints is a metaphor of the flesh burdening the soul. It is interesting to note the various marks left alongside the block of marble, above all at the back of the unfinished sculpture.

The Young Slave

The Young Slave (marble, height 256 cm, circa 1530-34)

Across from the Awakening Slave is the so called, “Young Slave.” The figure is more clearly defined, but seems almost bound within himself, burying his face in his left arm and hiding the right one around the hips. The contrapposto pose is quite exaggerated by the narrowness of the block of stone and by the slightly bent knees. The profound study of human anatomy is highlighted in the left elbow and the careful lines of the bent biceps and triceps. His face, which is just beginning to emerge, seems so youthful by comparison with his musculature. Michelangelo always chiseled out the image front to back: it clearly shows within the Young Slave, which appears to be emerging from the rock that shows the rough tracks of the large tooth chisels.

Detail of chisel marks left on the Young Slave

The Bearded Slave

The Bearded Slave (marble, height 263 cm, circa 1530-34)

The third statue on the left of the corridor, is the “Bearded Slave” the most finished of the four Slaves. The figure is almost free, only his hands and part of his arm, probably planned to hold a cloth, are unfinished. The face is covered by a thick, curly beard and the thighs are bound by straps of cloth. The torso is finely modeled, revealing Michelangelo’s deep knowledge of anatomy.

The Atlas Slave

The Atlas (marble, height 277 cm, circa 1530-34)

Down the corridor on the left is the “Atlas Slave.” The male nude seems to be carrying a huge weight on his head. Hence he is named after Atlas, the primordial Titan who held up the entire world on his shoulders. His head has not emerged from the stone, leading the slave to support and push such a heavy weight, which threatens to compress him. The force of weight pushing down, and that pushing back up, create a vigorous tension. There is no feeling of equilibrium here, only an eternal battle of forces threatening to explode in both directions. This pressure generates a power which perhaps more than the other Slaves, expresses the energy of the figure struggling to emerge from marble.

Two additional, superb Slaves, the Rebellious Slave and the Dying Slave (both ca.1510-13), are now displayed at the Louvre Museum in Paris. Giorgio Vasari explains in the “Lives of the Artists” how they ended up in France: “in Rome, he (Michelangelo) finished entirely with his own hand two of the captives, divinely beautiful figures, and other statues, than which none better have ever been seen. But in the end, they were never placed in position, and those captives were presented by him to Ruberto Strozzi, when Michelagnolo happened to be lying ill in his house: these captives were afterward sent as presents to King Francis, and they are now at Ecouen in France”.

The Rebellious Slave and Dying Slave, at Louvre Museum, Paris, France