Hall of the Prisoners

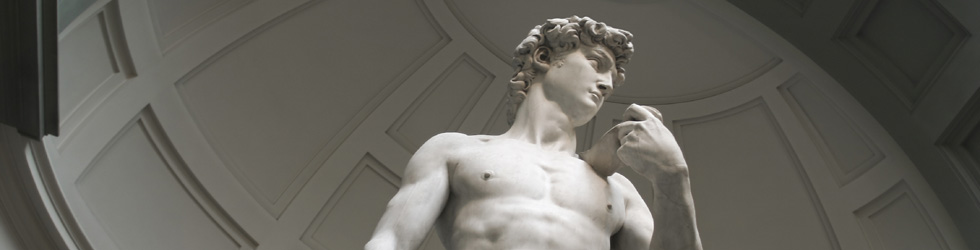

Used in the nineteenth century to display ancient paintings from the various collections, the Galleria was later altered to house the unfinished statues by Michelangelo, thus creating a specific, unified itinerary that culminates in the center of the Tribune where Michelangelo’s David stands under a halo-like dome.

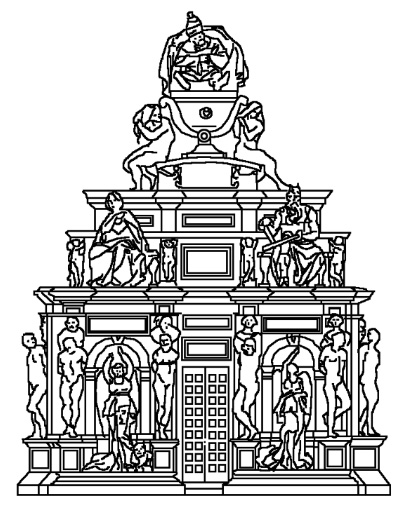

The Hall takes its name from the four large sculptures showing male nudes known as the Slaves or Prisoners or Captives. They were begun by Michelangelo for a grandiose project for the tomb of Pope Julius II della Rovere. The first commission dates back to 1505, before the assignment of the Sistine Chapel (1508), and it was meant to be the most magnificent tomb of Christian times, composed by more than 40 figures. The four Prisoners were carved for the pillars on the lower level of the tomb, intended for the grand Basilica of St. Peter’s in Rome. Michelangelo spent months in the Carrara quarries to personally select the brightest marble he likes necessary, marking each selected block with three circles. Due to a mounting shortage of money, the pope ordered him to put aside the tomb project in 1506.

Reconstruction of the project by Michelangelo for the Julius II Tomb dated 1505 (1st project). Inspired reconstruction by F. Russoli, 1952

The original design was later scaled down to less grandiose proportions after the pope’s death in 1513, then in 1521 and eventually again in 1534, when the Prisoners were no longer part of the project and thus remained in Florence. After about 40 long, conflicted years, the “tragedy of the sepulcher”, came to an end. Over this period, Michelangelo actually created some of his finest sculptures, all destined for Julius’s II tomb, including the Moses (ca. 1515) and the much-reduced funerary monument now located in another, but more minor, St. Peter’s church in Rome called San Pietro in Vincoli. Michelangelo envisioned a funerary chamber, decorated with statues depicting figures of the Old and New Testaments as well as allegories of the Arts, and the Virtues triumphant over the Vices. His “Prisoners” were to be an allegory of the Soul imprisoned in the Flesh, slave to human weaknesses.

After the artist’s death, four of the Prisoners were found in his studio and his nephew Leonardo Buonarroti donated them to Duke Cosimo I Medici, together with the Victory housed in Palazzo Vecchio today. In 1586, Bernardo Buontalenti placed the Slaves at the corners of the large Grotto in the Boboli Gardens of Palazzo Pitti. The walls of this ambiance are decorated with fake stalactites and stalagmites, carved sponges, stones and shells that are laid out to resemble anthropomorphic figures. These elements were meant to resemble a natural grotto, perfectly suitable for Michelangelo’s unfinished sculptures. The Prisoners remained in the Grotto until 1908 and transferred into the Accademia Gallery in 1909.

Read more on Michelangelo’s Slaves »

The Main Artworks along the Walls

With the arrival of David and the Prisoners inside the Gallery, the arrangement of the museum radically changed. In October 2006, several paintings by artists closely connected with Michelangelo, such as Fra’ Bartolomeo, Pontormo, Granacci, Andrea del Sarto and Michele di Ridolfo del Ghirlandaio, were placed alongside the Hall of the Prisoners to witness their friendship and mutual influence.

The main paintings along the Hall of the Prisoners are the ones highlighted and labeled in blue below:

Fra’ Bartolomeo’s The Prophet Isaiah and The Prophet Job (on your left as you enter the hall)

These two panels were formerly placed in the Basilica of SS. Annunziata in Florence inside the private chapel belonging to rich merchant Salvatore Billi. Both works were painted by Frà (brother) Bartolomeo immediately after his journey to Rome (c.1515), to be displayed next to a central “Salvator Mundi”, a religious subject chosen as a reference to the name of the rich patron Salvatore. Evidence of this reference is also showed by the scrolls in Latin:” ECCE DEVS SALVATOR MEVS”. The prophets feature solid volumes and vibrant tones, a clear evidence of his meditations on Michelangelo’s figures painted in the Sistine Chapel. In this mature work of art note the use of a few bold colors such as dark blue, raspberry red and strong ocher yellow, inspired by the powerful figures of Michelangelo. Cardinal Charles of the Medici family purchased the panels in 1631 for his private apartments, which were then exposed at the Uffizi and eventually at the Accademia Gallery.

Andrea del Sarto’s Christ as the Man of Sorrows, on the right wall, between Michelangelo’s St. Matthew and the Bearded Slave, detached fresco painting

This detached fresco depicts Christ seated in a grotto with the instruments of his passion with the wounds from his suffering in full view. This image conforms to the iconography of the “Vir dolorum” (Man of Sorrows), a theme very common in the 15th century, but rather rare in Tuscan art during the first decades of the Cinquecento. The fresco, a work of great beauty which attests to the mastery of Andrea del Sarto as a draftsman and colorist, was completed during the second decade of the Cinquecento for the Church of SS. Annunziata in Florence. Andrea del Sarto was a Florentine painter highly regarded during his lifetime as the “pittore senza errori” (the faultless painter). He belonged to the first generation of Mannerist painters showing great admiration for Michelangelo’s lessons, but keeping a soft and balanced atmosphere within his creations.

Michelangelo’s drawing on the left, Ghirlandaio’s Ideal Head “Zenobia” on the right

Michele di Ridolfo del Ghirlandaio’s Ideal head (oil on panel) circa 1560-1570 (to the right of Pontormo)

The portrayed woman seems to be a graceful revision of the “ideal head”, referring to some of Michelangelo’s drawings. In particular, this oval portrays a woman in profile identified as Zenobia, an ancient queen as well as a fearless warrior and a strong, virtuous and beautiful woman. Zenobia stands out from a green background, with her elaborate coiffeur, a sensual glance seeming to follow the spectator with a courtesan’s alluring gaze.

Michele di Ridolfo del Ghirlandaio’s Ideal head (oil on panel) circa 1560-1570 (left of Pontormo)

This painting, created between 1560 and 1570, can be considered a companion piece to the other oval painting described above. Both ovals were found in the Grand-ducal collection, but are originally from a Florentine convent. The intricate braids, the pearls adorning the hair, the earring, the ring and the gold necklace confer on this image a lighter, more decorative tone than the one encountered in the Michelangiolesque prototypes of 1524.

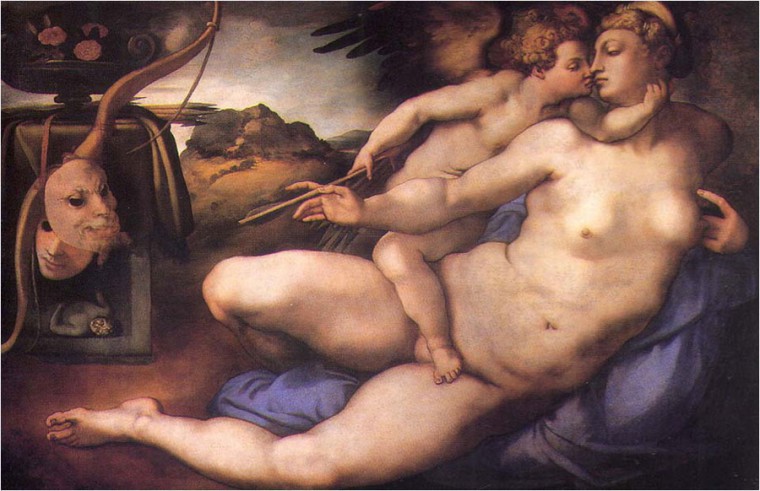

Pontormo’s Venus and Cupid based on a drawing by Michelangelo

Pontormo: Venus and Cupid (oil on panel, painted on preparatory cartoon by Michelangelo) ca 1533.

The panel was painted around 1533 by Jacopo Carrucci, nicknamed Pontormo. Michelangelo was still working in Tuscany before his last departure to Rome in 1534. The painting was part of a sophisticated decorative program about love and poetry. According to Vasari’s chronicles, around 1533 Bartolomeo Bettini commissioned Michelangelo to draw a cartoon portraying “a nude Venus with a Cupid who kisses her” for his private residence in Florence. Pontormo painted the subject accordingly, but the sensual nude body of Venus was covered by a drapery soon thereafter. The panel has been recently restored and shows the original beauty of the Goddess. The attitudes of the two figures seem to embody the Renaissance theory of love: the earthly love driven by senses (Cupid) and heavenly love (Venus), turned towards the divine.

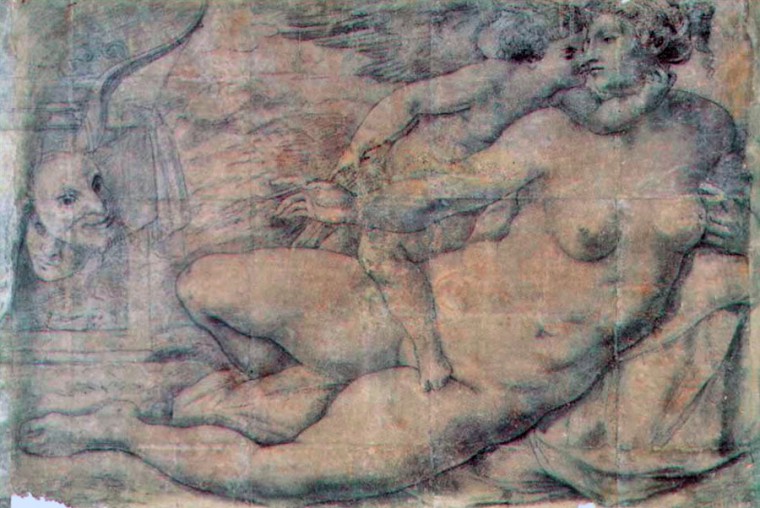

Michelangelo (attributed to), drawing for “Venere e Amore”, carbon, 1310 x 1840 mm, 1533c.

Naples, National Museum and Galleries of Capodimonte, inv. 86654

Bronze bust of Michelangelo by Daniele da Volterra (to the right as you enter the Hall)

Bronze bust of Michelangelo by Daniele da Volterra (to the right as you enter the Hall)

Daniele Ricciarelli (1509-1566), better known as Daniele da Volterra, was an Italian mannerist painter and sculptor. He is best remembered for his association with the late Michelangelo. Several of Daniele’s most important works were based on designs made for that purpose by Michelangelo. After Michelangelo’s death, Daniele was hired to cover the genitals in his “Last Judgment” with vestments and loincloths. This earned him the nickname “Il Braghettone” (“the breeches maker”). Toward the end of his creative life, Daniele da Volterra turned his back on painting and began devoting his time to sculpture. After his death, numerous artworks were found in his house in Rome, in which Michelangelo had once lived. Daniele’s estate inventory lists a total of six bronze busts of Michelangelo in varying degrees of completion and finish. Daniele cast this bronze bust depicting an elderly Michelangelo, witnessing the old age of the friend. Michelangelo lived a very long an productive career, working until the last months of his exceptionally long-lasting life. He died in Rome at the age of 89. Read more about Michelangelo’s life here.